Gardens and landscapes have been depicted in art and wall murals since antiquity, but after the fall of the Roman Empire they became representations for religious and figural scenes. It was not until the 16th century that artists began to look at them as worthy of depiction in their own right.

The word ‘landscape’ derives from the Dutch, meaning landschap and became a popular term during the 1500s when the Dutch artists developed the subject more seriously. Looking through such paintings and drawings, the viewer can see a record of not only the changing landscape, but of how people felt at the time about the world around them. The same thought applies to textile design over the centuries, reflecting not only the growth in world-trade but also the trade in plants, agriculture and broadening travel.

Textiles have always been a part of this story, whether in the paintings themselves, as the fabric worn by the figures or within the interiors depicted, but also in the room that the completed painting would hang. Textiles, like paintings, tell a story and often say as much about the wearer, their beliefs and the story that they want to express to others. Nature and our landscape has always been a part of this narrative and the plants and flowers within them grew to become symbols and tell a story of their own.

Flowers, such as the tulip, which had once originated from the mountains of Turkey, became the most desirable flower on earth and during the height of Tulip Mania in 1637, one ‘Viceroy’ bulb sold for the equivalent of £2,500 in today’s money and a ‘Semper Augustus’ sold for over £6,000.

The tulip became a symbol of not only luxury, but also expressed the wearer’s knowledge of travel and fashion. Its stylised form woven and printed on to cloth created a conversation piece where ever it was worn.

Detail of hand woven Spitalfields silk, 1743- 1745, showing the tulip floral motif

The Huguenots were attributed to bringing the art and pleasure of gardening to the overcrowded Spitalfields and Bethnal Green, with hanging baskets filling the narrow alleyways, used for not only pleasure, but as a way of growing the much needed plants for dyeing their silks.

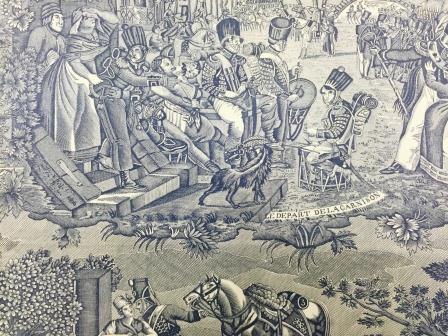

By the late 18th century, and with the ever increasing industrialisation of the countryside, the pastoral landscapes became idealised within art, and the fashion made popular by Marie Antoinette. These stylised landscapes as a repeating and printable motif, known as a toile de jouy could be manufactured in large quantities for the general population and not for just for the elite.

Document 823 – toile de jouy pastoral scene c.1800s

As technologies improved and with the introduction of copper roller printing in manufacturing during the 1780s, more detailed patterns could be reproduced at cheaper cost. Often the outline of the design was printed by the copper roller, and the areas of colour were still being blocked in by hand up to the mid-19th century.

Roller Printed Cotton with colour in fill, French c.1800s

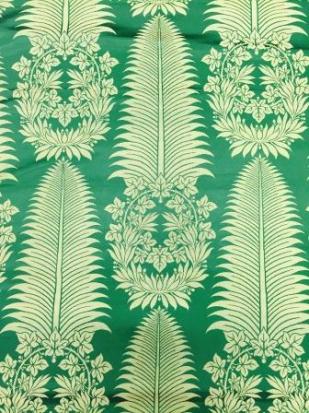

As the style for idealised landscapes changed within art the artists were experimenting with painting outside, plein air, and creating a closer connection with their natural surroundings. This fertile ground gave birth to movements such as the Pre Raphaelites and designers such as William Morris, where the representation of nature rose to the greatest importance within their design philosophy.

Tudor Rose, designed by William Morris and printed by Warner & Sons

Towards the end of the century the fashions looked back again to the 18th century for their inspiration, before grasping on to the elaborately organic forms of the Art Nouveau and then into a more dynamic decade of the Jazz Age. Here natural forms were stylised with what we would consider a graphic or illustrative hand, which filtered through to every average home. Following WWI there was a yearning for more peaceable times and nostalgia for the Tudor period, giving life to the ‘Tudorbethan’ style.

Hand block printed silk by Warner & Sons from the late 1920s showing busy floral pattern

Tapestry, power woven fabric from the 1920s, early 1930s by Warner & Sons – design taken from Tudor needlework

The mid-20th century threw many of the formative traditions out of the window, but interestingly remained true to showing nature and landscapes but with a new vigour, style and colour palette. The introduction of screen printing in main stream manufacturing after WWII allowed for greater flexibility within design and encouraged not only innovation, but an ability to refresh designs seasonally.

Green Pastures, screen printed by Warner & Sons, 1953

Design Director from the late 60s onwards, Eddie Squries, encouraged the in-house studio to experiment with ideas and challenge what had become a conservative high-end decorator’s market. The bold designs of the 1960s and 70s, showed Warner & Sons’ ability to combine modern style with traditional form and ensured they remained leaders in the industry.

Yentai, printed cotton, Warner & Sons, designed by Eddie Squries, 1966